“Since the advent of the CD, listeners have been deprived of the full experience of listening.” - Neil Young PonoPlayers...

Read More »

NPR on the Audiophile

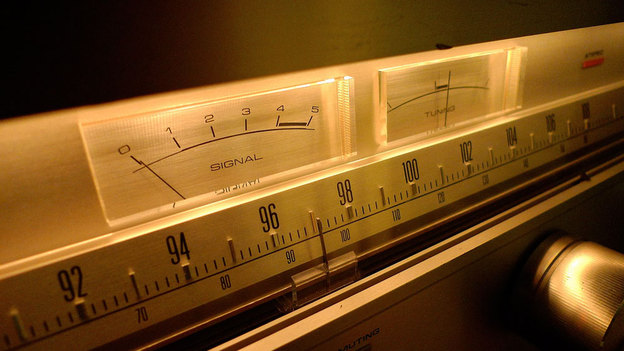

A VU Pioneer TX-9500 II

This NPR essay was posted on Georgia Public Broadcasting’s website:

There are still people willing to drop a large chunk of their income on the best audio equipment available,

says music professor Mark Katz. “That said,” he adds, “the landscape or perhaps soundscape has changed.”You may remember the type: Laid-back in an easy chair, soaking in Rachmaninoff, Reinhardt or the Rolling Stones, enveloped by the very best, primo, top-of-the-line stereo equipment an aficionado could afford.

In robot-like, 1980s cadence, the audiophile could rattle off favorite components, which might include an all-tube Premier One power amp by conrad-johnson, a Sota Sapphire turntable, an Ortofon MC-2000 cartridge and a pair of Magneplanar speakers.

Geeky? Mos def.

But the audiophile was a symbol of the Golden Age of Audiophonics, a time when certain people worshiped at the altar of expensive high-fidelity, two-channel stereo equipment. They were knights errant on an eternal quest for audio perfection the exact replication of an original performance.

Here is the way one New York Times writer described a Holy Grail system in 1980: “There is a greater transparency of orchestral textures, giving each instrument an almost tactile presence.” The theological debates pitted vacuum-tube amplification advocates against those preferring solid state, or transistorized, amplification. The sacred texts were magazines such as Stereo Review and High Fidelity. Stereo stores were the holy shrines.

Then came the barbaric revolution. The boombox, the Walkman and other hand-held devices made music more portable. Digital sound enabled listeners to store scads of compressed, easy-to-download music files first on computers, then on miniature devices and cell phones. Quality in recordings was sacrificed for speed and convenience. Loudness became more important than clarity. The richness and warmth of a recording was replaced by tinniness and splash.

Now it’s 2011. And amid all the earbudded iPods, smart phones and MP3 players, one can’t help but wonder: Whatever happened to the audiophile?

The Soundscape Has Changed

“There are still people who passionately pursue the highest possible sound quality in their playback equipment, and are willing to spend large portions of their income to the best speakers, amplifiers or turntables,” says Mark Katz, an associate professor of music at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and author of Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music. “That said, the landscape or perhaps soundscape has changed.”

Sound quality is rarely brought up in music conversations these days, Katz says, and for many listeners high-fidelity is a non-issue, “especially given that people often listen to music in noisy environments.”

Listening to music used to be a plop-down, stay-still event. Now it’s something people do while doing something else, like eating while driving or chatting on a phone while walking. The experience of listening to music these days, says Timothy Doyle of the Consumer Electronics Association, is “not unlike personal computing: It’s a 24/7 multilocation proposition; people are taking their music with them, and as a whole, the world has changed so that there are simply fewer and fewer ‘old school’ proponents of sitting down and listening to music.”

Cue up the statistics: In 1998, The New York Times estimated that high-end audio sales totaled approximately $500 million a year. In 2010, the CEA says, sales were around $200 million.

Defining high-end audio is a tricky task, says Doyle. And “it’s not entirely a matter of declined sales so much as sales being spread out across a wider spectrum of products and companies.” He points out that price deflation and international competition also affect the sales numbers.

But “the key takeaway here,” says Doyle, “is that the market has shrunk not grown.”

And maybe, Doyle and others suggest, the audio market is moving into a metamorphosis stereo-style.

On one channel: While the sales of high-end devices that deliver high-quality sound may have decreased, the sales of low-end devices that deliver better and better audio quality such as those sold at big-box stores is on the upswing.

On the other channel: Some media consumers who in the past would have been known as audiophiles have turned their passions and paychecks to other delivery systems, including Brobdingnagian flat-panel TVs, home theaters and multiroom audio-visual contraptions.

No Longer Locked Into A Format

To Jon Iverson of the Stereophile website, audiophiles are forever moving in direct rhythm with and in syncopation to mainstream music lovers.

“The mass-market selects and audiophiles perfect,” he says. “Vinyl playback was first a mass market success, and audiophiles set about perfecting it and still do. CD was next and audiophiles and high-end audio companies spent the last several decades perfecting disc-based audio technology. This will always be so.”

The optimistic upshot, Iverson says, is that the online/download digital world is, in fact, “the biggest opportunity for audiophiles so far.” And, as audiophiles push companies to perfect how good music can sound via the Internet, the Second Golden Age of Audiophonics might be dawning.

“It started out a bit rough with compressed MP3 and iTunes files that, quite frankly, sound OK but not that great,” Iverson says. “But the mass market has clearly accepted online music. And we’ll see these formats push to higher resolution as bandwidth allows. We are already seeing this with iTunes and websites like HDTracks.com.”

There is also a vast underground online community of high-resolution file traders who demand better and better transfer technology for all types of music, Iverson says. “It’s fascinating to see the discussions of which mastering of a classic title is best. There are first release, remasterings, special editions, Japanese versions, et cetera, and then quite a few ways to transfer these titles in full resolution to a hard drive from disc.”

Iverson gets jazzed at the possibility that Apple will introduce higher-resolution iTunes. “But here’s the point,” he says. “Since we are no longer locked to a physical format like LP or CD, there is far more flexiblity in introducing higher resolution audio formats in an online world. So the potential for audiophiles is greater than ever before to have a format aimed at them that coincides with the mass market.”

And maybe even high-quality audio equipment you can buy at a big box store.

Surrounded By Sound

On the home-theater front, Mike Mettler, editor-in-chief of Sound + Vision magazine, sees many audiophiles becoming videophiles. “As the home theater boom truly began to explode over a decade ago,” he says, “audiophiles dove into it relatively willingly, as we also appreciate the benefits of watching a great picture on a great screen or TV. But it all ties back to enhancing our inherent passion for great sound.”

To Mettler, great sound these days is found “by hooking up high-definition TVs to surround-sound systems.” Also known as 5.1 systems, the six-speaker configuration is made up of left and right front speakers; a center channel, mostly for dialogue; left and right rear channels and a subwoofer the 1 in the equation for the low-end of the audio spectrum. You can also buy 7.1 and 11.1 systems.

Such conglomerations, Mettler says, “mirror the 360 degrees of audio that we deal with in everyday life, and they serve to enhance the overall audio-visual experience. Think of the excitement of feeling like you’re in the middle of a roaring stadium crowd while watching football in high-def. Or hearing a car literally drive across the soundstage and into the distance behind you to correspond exactly with what you see that car doing onscreen.”

Surround sound “makes you feel like you are there,” Mettler says, and “that’s one major way the audiophile world intersects with video. When the A and the V are working in tandem, it’s a beautiful thing indeed.”

‘Totally Obsessed With Sound’

Parts of the debate are just so much noise to Laurie Monblatt, a Northern Virginia painter and sculptor and unapologetic audiophile.

“I guess I am what you might describe as totally obsessed with sound,” Monblatt says. “I have had this disease for over 30 years. My adventures in sonics began when I was 15; I am now 56. I grew up in Northern New Jersey and could be found at the Fillmore East or The Bottom Line, as well as many other venues, most weekends.”

She adds, “My passion for music was tremendous and remains so to this day.”

Let’s let Monblatt describe her system: “I have a dedicated two-channel listening room. My passion is for vacuum tubes and this set up consists of a KT88 based tube amp, tube preamp, tubed CD player, tubed digital-to-analog converter that is partnered with an iMac for digital files and wonderful pair of very efficient speakers. Power to the room is on dedicated lines.”

Over the years, “many components have come and gone both solid state and tubed,” she says, “but as my obsession grew it became obvious to my ears that tubes give me more of the ‘real thing’ regarding texture, bloom, soundstage and tone. I could go on and on …”

Every single component in her listening room is strategically placed to make the sound perfect. The walls are acoustically tuned to ensure a more accurate listening environment.

When she sits on a comfortable sofa, in exactly the one spot where all the sound comes together, and she listens to Paul McCartney singing Blackbird, she can hear it so perfectly that she can discern McCartney slapping his thigh against blue jeans. It’s a really distinctive slap sound, she says, and quite different than if Sir Paul wore wool pants.

There is no video equipment in the listening room at all. And when Monblatt settles onto the sofa, she doesn’t read or text or talk.

So if you ever want to ask Laurie Monblatt where all the audiophiles have gone, that’s where you will probably find her. In her sanctum sanctorum of sound. Just her and her music.

NPR editor Marilyn Geewax and several audiophilic friends of NPR contributed to this report.